Reimagining Waste: How Management Practices Shape Economic Circularity

Historically, the flow of goods and materials through society has been described as a linear economy that involves the supply chain (i.e. production and distribution of goods) and subsequent activities including use and disposal. The environmental movements of the 1970s and 80s emphasized the finite nature of our planet’s resources and an acknowledgement that humans can and do impact the environment when utilizing these resources. This birthed a variety of initiatives from minimizing resource use at the top of the supply chain to the creation of modern recycling facilities, formation of residential recycling programs, conversion of incinerators to waste to energy facilities and evolving landfill practices via the EPA’s Subtitle D legislation into highly-engineered waste containment facilities.

These changes demonstrated our ability to protect the environment while recovering and reusing materials. Over time, the idea grew that it might be possible to shift from a linear economy to one in which most societal materials could be captured and re-used. While early philosophical roots are traced back to the 1960s, the term “circular economy” was explicitly used to describe the concept in 1988 in a scientific paper by economist Allan Kneese. Since that time, the circular economy concept has evolved to become the basis for how to address issues like climate change, resource minimization and ecosystem preservation.

Both the linear and circular economy concepts include the same phases:

- Resources – raw resources used for manufacturing

- Manufacturing – creating goods and products

- Delivery – storage, transport and distribution of goods and products to the end user

- Use – consumption of goods and products

- Disposal – discard of unused goods/products or related materials (e.g. packaging)

The primary difference between the two lies in how materials are managed post-use: in a linear economy, they are merely discarded, whereas, in an ideal circular economy, they’re reintroduced as resources, either recycled, repurposed, or converted for beneficial uses such as energy. In a linear economy, end of life represents no re-use or end use of the materials, but in a circular economy, the disposal of goods becomes an input back into the resources phase.

A critical question is which phases have the ability to “bend” or “curve back” in order to create circularity? By shifting disposed materials from an output to an input, the disposal stage actually transforms a linear economy to a circular one. Although other strategies, like waste minimization, contribute, they minimize resource utilization but do not increase circularity. Untapped resources simply stay put as a resource and aren’t reintroduced as part of the economy. This illustrates that waste management activities, including diversion (e.g. recycling, composting) and beneficial use strategies (e.g. anerobic digestion, waste to energy), are what literally create circularity.

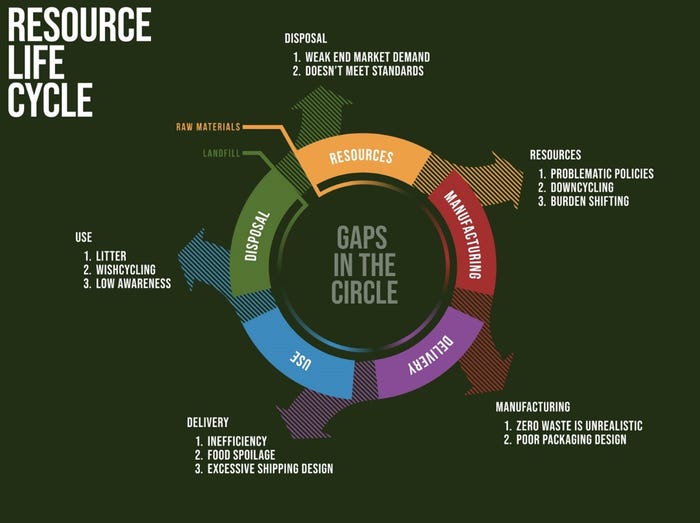

Despite diagrams often depicting the circular economy as a neat, closed loop with one input and one output, the reality is more complex. Rather than a circle, the circular economy in its non-idealized form looks more like a pinwheel. Because no process is 100% efficient, each stage spins off discarded waste materials due to a variety of factors that include industrial/manufacturing wastes, inefficient distribution systems, less than perfect consumer behavior and challenges in managing waste materials at end of life (see the graphic below for some examples).

To achieve greater circularity, every stage of the process needs strategies to consistently use discarded materials as resources. While the supply chain has mainly focused on waste minimization—easier to manage within factories and warehouses—true circularity demands collaboration across all industries. Historically, this collective effort has been lacking. The goal is to treat waste as a valuable resource, incorporating it back into manufacturing. However, progress has been slow. As the industry evolves, it faces new challenges and hurdles, often requiring advanced research or data collection. Overcoming these challenges is essential; otherwise, a fully circular economy might remain out of reach.

By Dr. Bryan Staley